We interviewed a number of influential harm reduction and drug policy reform advocates from across the country. These are the people who are working against incredible odds, are largely unrecognized and serve as inspiration to the wider harm reduction community. Our aim is to amplify hope by telling their stories, uplift the people and programs delivering harm reduction services, and raise awareness about the strength and resilience of the harm reduction community across the U.S.

Here Are 8 Harm Reduction Champions We Want You to Know

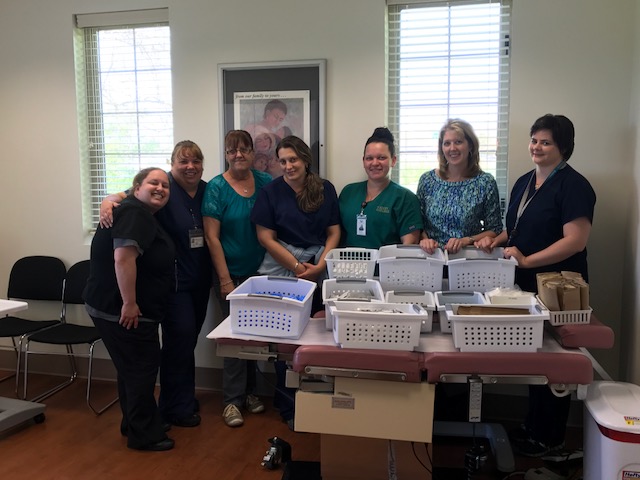

Joelle Puccio, Traveling NICU Nurse, Board Member People’s Harm Reduction Alliance & National Perinatal Association.

Location: somewhere on the road.

Please tell the harm reduction community a little about yourself.

From first grade until college, I was homeschooled in a rural area by conservative Christian parents. My parents were very active in local politics, at least before all the rest of my siblings were born. My Dad ran a campaign for a friend who was running for local office, and there are photos of me as a toddler with my mom at an anti-choice rally, holding a big sign dripping with red paint. I was a gymnast until I was 16 years old, and I won the Level 4 Washington State Championship when I was 12.

My first drug use experience was when I was a toddler, drinking a bottle of Dimetapp that had been left out on the bathroom counter. I don’t remember it, but it sounds like it was fun. After that I didn’t use for about a decade, and then my adolescent use was pretty typical. I’ve tried most of the normal stuff, but I really love stimulants. I remember walking to the coffee shop with friends at about 13 and drinking two 24oz espresso drinks each. I didn’t even realize that I’d smoked heroin until a few years ago, because the boys that gave it to me always called it opium, which I was into, because I’d always loved Sherlock Holmes.

Around age 10, I started a business selling eggs from our chickens to friends and family, and my Dad helped me make my own cards with my folksy business name on them: “Jo’s Eggs”. I was always very into capitalism. I was constantly trying to make money off my siblings. One time, I loaned my brother $10 for a week and made him sign a contract that for every day he was late paying me back, he would owe an additional dollar. He forgot, as I knew he would, and I neglected to mention it for a couple months, and then brought him the contract and demanded that he pay. It went about how you’d think. My Dad made him pay up though, since I had his signed contract, but told me to never ever enter into a contract with a sibling ever again. At 14 years old, I started working as a gymnastics coach, and went to college. I got my first Associate degree just a few days after my 17th birthday. I moved out of my parents’ house at 18, and quickly realized that I hated being poor and hungry. So I worked 3 jobs and put myself through nursing school over the next 7 years.

After 13 years at a hospital outside of Seattle, I’m now working as a traveling nurse. That means that I have an agent who sets me up with 3 month jobs at various hospitals around the country. I’m on the Board of Directors for the People’s Harm Reduction Alliance (PHRA) and the National Perinatal Association (NPA). Through NPA, I am working on creating guidelines that will radically change the way we treat pregnant and parenting people who use drugs. I travel the country in my RV with my wonderful partner and our 2 cats. I’ve attended conference calls for my various projects while driving through rural Indiana, from the edge of the Grand Canyon, and at a truck stop in Oklahoma. I’ve attended DIY punk shows on both coasts and in between. I’ve seen the wildly different policies for treatment of pregnant and non-pregnant people who use drugs in various regions. Once I get a couple more years of travel under my belt, I plan to go back to school and get my PhD so I can train up the next generation of harm reductionists.

How did you first become involved in harm reduction?

Like most kids, I knew that everything I had been told about drugs was complete nonsense. Even in nursing school, the substance use education we got was more of the same. When I had a service learning assignment, I went to PHRA and volunteered with the syringe access program. This was the only place I had ever been where I heard factual information about substance use. As I began to do my own research, I realized that the education I had received elsewhere was even more bizarre than I had realized. I saw that research results were misinterpreted routinely, and that even so-called scientists seemed to think that paternalistic misinformation was preferable to telling the truth. I realized then that drug policy and education was an area where I could easily create positive change, because the work that was being done was so terrible that to improve upon it wouldn’t be hard at all.

What is your most memorable experience doing harm reduction work?

Often when I was working the syringe access table at PHRA, we would get aggressive people coming by. The Seattle site operates from a folding table set up in an alley, and at night, when we were working with an all-femme staff, people would wrongly perceive us as vulnerable. It’s never participants, usually just guys who wander over to hit on us, thinking we’re having a bake sale or something, and then getting angry that we don’t conform to their idea of what a lady should be. One time, I was there with only one other volunteer and a guy started getting really aggressive, yelling and throwing his stuff around and calling us names. I was mostly just worried that he would keep others away from service, but there was nothing we could do about it, so we settled in to wait for him to run out of steam. Then one of our participants came up to the table, noticed what was going on, and instantly went mama bear on his ass. She pulled out her Taser, chirped it at him a couple times, and yelled, “You think it’s ok to threaten women? You leave these ladies alone! You think they’re out here in the freezing cold at night because it’s fun? No, they’re out here because they believe in harm reduction and helping others!” People outside of harm reduction often ask me how I keep myself safe from the people that I serve, and I laugh. I’ve never felt safer than when I’m at the syringe access program, surrounded by the loving and supportive community of people who use drugs.

What do you think are the most important harm reduction messages regarding perinatal drug use?

Illicit drugs are not as bad for babies as we’ve been led to believe. I’m not saying that every pregnant person should go out and start a habit, in fact I would advise any pregnant person not to use recreationally at all, including caffeine and cannabis. What I am saying is that there is simply no evidence to support the harms that our society blames on perinatal substance use. In scientific research, perinatal substance use is associated with negative outcomes. It is important to note that associations are not a cause and effect relationship.

Good research is difficult to perform and interpret, entirely due to the legal and ethical status of substances. It is impossible to design a randomized controlled trial where you take group of pregnant people and tell half of them to smoke meth because you want to find out if it hurts their baby. Because of the threat of criminal and child services consequences, the only families that we are able to study are those that have been caught. This results in sampling bias where the families in studies are more likely to be poor, to have experienced racism, and to be involved in the criminal justice system. When we look at families with poverty, trauma, social and systemic oppression, they are at higher risk for poor pregnancy and childhood outcomes, with or without substance use.

It is nearly impossible to separate the effects of substance use from the effects of other social determinants of health. When studies attempt to do so, they find little to no effect. Another problem with the way knowledge is produced is that it is nearly impossible to publish results that do not conform to the idea that “Drugs are bad, mmmkay?” or to get funding for a study that looks at benefits of substance use. Studies are defunded or unpublished because they truthfully report and analyze their results, without reinforcing the harmful, false scaremongering propaganda that passes for scientific fact these days.

The way our society responds to perinatal substance use is BY FAR more harmful than any substance effects. In order to create useful knowledge and policies about the actual effects of perinatal substance use, we need to radically change the way we treat women and other people who can become pregnant. We need:

- Complete decriminalization of all substance use

- To support, not punish pregnant and parenting people struggling with problematic substance use

- To smash the patriarchy that forces women and other people who can become pregnant into second class citizenship, makes us vulnerable to violence and oppression, and pays us less than men for the same work

- To smash the law enforcement industrial complex that tears families apart and creates special classes of crime that can only be committed by pregnant people

- To smash individual and systemic racism that incarcerates the parents of black and brown children at many times the rate of white children despite similar rates of substance use

- To smash the system of capitalism that devalues the so-called women’s work of birthing and rearing the next generation and destroys the environments in which we live

Until women are free and equal members of society, allowed to choose what we put into our bodies, and when and if to become or remain pregnant, we can never meaningfully address the issue of perinatal substance use.

What are your suggestions for incorporating gender-sensitive harm reduction into existing programs?

Harm reduction is overwhelmingly run, controlled, and designed for and by white cismen.

Put women, trans* folks, and non-binary people into positions of leadership. Create space for diverse voices by getting out of the way. Value the contributions of people with lived experience and put your literal money where your mouth is. Hire women and QTPOC and pay them a living wage. Provide childcare at your next event. Think about how someone with history of oppression based on gender or sexuality experiences your service. Do you use inclusive language in your signs and flyers? Are there diverse faces waiting to greet them when they walk in?

Make yourself replaceable, and replace yourself with someone who doesn’t look like you. If you’re having trouble recruiting diverse voices, it’s not because they aren’t there, it’s because you need to change something about what you’re doing.

What continues to motivate you to do harm reduction work?

Every time I am forced to participate in breaking up a family because of perinatal substance use, I die inside. The trauma that I, as part of the medical system, help to inflict on women and children haunts me daily. The barriers to success that our system imposes on these families are insurmountable. The problems are urgent. There is nothing more horrifying than what the medical, criminal, and child welfare systems do to families with substance use. Faced with this situation, I cannot imagine not doing harm reduction.

Any final comments?

I have noticed that even in the harm reduction community, the information I present is met with skepticism. If anyone reading this wants to learn more, and come to their own conclusions, I encourage you to look at the work of Lynn Paltrow, Jeanne Flavin, Melanie Dreher, Ronald Abrahams, Susan Boyd, Lenora Marcellus, Carl Hart, and Mary Hepburn. Look at the Ottawa Prenatal Prospective Study (OPPS), the Maternal Health Practices and Child Development (MHPCD) study, and the Infant Development, Environment, and Lifestyle (IDEAL) study. Look at the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) and follow up on citations of claims of harm from substance use. I can provide you with more reading and I would love to talk with you and improve my own understanding.

Lastly, if you are pregnant or parenting with substance use, I want to hear from you. I want your stories, questions, and expertise. Please give me the honor of working with you to continue to improve outcomes for the families of the future.

Malika Lamont, Opioid Response Manager, Cascade Pacific Action Alliance, WA.

Please tell the harm reduction community a little about yourself.

Right now I am the Opioid Response Manager for the Choice Community Health Network at the Cascade Pacific Action Alliance, an accountable Community of Health for the Medicaid Transformation Demonstration Project. We serve seven counties in central southwest Washington, ranging from frontier to urban. I consult with the National LEAD program. I’m on the board for Behavioral Health Resources — a local mental health service agency here in SW Washington state. They also have programming for pregnant and parenting women. I also consult with an agency that works with pregnant and parenting people including those who use drugs. In my day job I hope to expand access to MAT, mental and physical health services using the hub and spoke program model. I’m also on the advisory board for the Bachelor of Science and Nursing program at St. Martin’s University and I am a preceptor for student nurses. I provide harm reduction training and program development in our community; for clinicians and organizations including training for operationalizing naloxone distribution policies in emergency departments and pharmacies. And let’s see… last year, 2017, I was honored by the YWCA as a Woman of Achievement for my work in public health and the community. Now I am applying to be on their board and getting more involved with their Economic Empowerment Program for women and girls.

I focused my graduate work on harm reduction based public health policy. With a focus on those most impacted and vulnerable. i.e. women and children. In collaboration with Alisa Solberg at PDAP we birthed the Washington Association for Syringe Service Program, a collaboration across the State of Washington of all of the Syringe Exchange Programs to educate legislators and decision makers about how their work impacts drug users. As a part of that work my friend and colleague Mileen Gilkey and I created a continuum of health for women who use drugs – with and without harm reduction and literature review to flesh out a definition of what harm reduction means for people who inject drugs for advocating to law makers and decision makers.

Serving women and improving the lives of women is really close to my heart, and important to me when I do this work. Some of the most powerful experiences I’ve had working in social justice and harm reduction has been working with Full Circle United, an advocacy group that is organizing Black and Indigenous women in response to police violence.

One of our accomplices in the struggle Leslie Cushman (2017 YWCA Woman of Achievement) drafted legislation that has become law. It requires law enforcement be trained to de-escalate situations, it changes the use of force law in our state, Amnesty International recognized Washington State as having one of the most egregious use of force laws in the U.S., because it gave de-facto immunity. FCU supported in a call to action 2 years ago after the murder of Philando Castille, people in our state collected over 360,000 signatures. A large collaboration of people and entities across our state. The Puyallup tribe, LEAD, Not This Time, Showing Up for Racial Justice, and a host of other entities. FCU did not endorse the initiative because we believe in dismantling the police structure as a whole. However, we organized and advocated on this bill for people who have lost family members to police brutality and have experienced police violence in Washington and throughout this country.

One other exciting thing I’m working on right now as the vice chair of the Asset Building Coalition is planning and advocacy for incorporating harm reduction into economic development initiatives. I want to figure out how we can bring harm reductionists to the table here because it’s one thing to do harm reduction in the streets, but it’s also crucial that we start talking to the wider community about how harm reduction can be a real asset – like when developers build these new high-rise apartment buildings, and then it’s a problem that homeless people are hanging out around the building and the people living in those apartments start to complain and call the police to get rid of them, or pay to gates put up to keep the homeless people away. Instead of letting this whole thing unfold and only thinking about the people living in these new fancy high-rises, why aren’t we thinking about collaborating to include low-income units in this building in the planning process? Because the fact is, putting up gates doesn’t solve the problem for anyone, it just wastes money that could be spent on making life better for everyone, and making this a great place to live. We have to ask ourselves, what is the price of being “right?”

All of the resources spent on managing the impacts of displaced people would be better spent housing and stabilizing people, not to mention it is the compassionate and actually right thing to do. If we as members of the harm reduction community are not at the table, I fear it will not even occur to anyone.

How did you first become involved in harm reduction?

I think I have always been a harm reductionist, I just didn’t have a name for it. I am a practical person and harm reduction makes good sense. I am also anti-establishment as hell, even though I may not look like it. My first time demonstrating these tendencies in a drug policy manner, probably was in High School, I used my International Baccalaureate science research project to analyze the chemical difference between crack and powder cocaine and used the analysis to ask the question how a molecule or chain of benign molecules could justify the sentencing disparities in the U.S.?

Once I had learned about this harm reduction thing in a named manner from my first ancestor in the movement, Pawnee Brown. I was big, pregnant and at a pretty shitty place in my life. Just having a name to succinctly describe what I had been doing all along at a time in my life when I was at a huge crossroads was really meaningful. I started working at the County in HIV Prevention. I had big feelings about working for the government, I felt like a sell-out. Pawnee took me under his wing, showed me syringe exchange, and took me to my first NASEN conference on my due date. When I was on maternity leave, two months later, Pawnee got sick and they wanted to shut down the exchange and I was like “no you can’t people are counting on this service!” They said “are you up to doing the job we hired you for and the syringe exchange?” I wasn’t sure, but I knew it couldn’t stop so I did both. It has been on and crackin’ ever since then.

During my time as director of the syringe access program in downtown Olympia, I worked to really build out our services and expand the program. We took on networking across counties for HIV prevention planning, education and capacity building, developing harm reduction trainings for chemical dependency professionals in harm reduction settings and political advocacy for syringe exchange (after work of course LOL) and harm reduction services throughout our region. I was on the state HIV prevention planning group and really had to fight for syringe access with our Department of Health. Locally during that time our program finally got to move indoors and have a real site for our program where we were able to expand our HIV counseling and testing services, start up a free wound care clinic, set up a low-barrier drop-in center, and beef up our referral services. Eventually we grew out of our first site space, and we got the opportunity to co-house our program with Capitol Recovery Center that uses a clubhouse model to serve people living with severe and persistent mental illness, and partnered for referral services.

I pushed for 10 years to get a county Naloxone policy passed and then one for county law enforcement that implemented trainings I had developed for law enforcement to administer naloxone, and expand access to these naloxone trainings in Thurston county. In addition to partnering with the Olympia Downtown Business Association to get a syringe access program indoors at a site downtown, I implemented a program to purchase mountable locking sharps containers after there was an uptick in improperly disposed syringes for their businesses, and collaborated with the street-based syringe exchange EGYHOP (Emma Goldman Youth and Homeless Outreach Program) to pick up the sharp containers and bring them to the program for safe disposal. So much of the work I did at this program really pushed for increasing the profile of need for harm reduction services in policy at the county and state level, and finding resources to sustain the work.

What is your most memorable experience doing harm reduction work?

Harm reduction really taught me how to really, truly meet people including myself where they’re at, and also just really being able to accept with grace where I was, and move forward from there.

When I moved on from doing direct service at the SEP downtown, and started working at a treatment facility briefly, part of me really felt like I was selling out, because the way we provide treatment services in this country commodifies people and it really bothers me. There was this one day, I’ll never forget it, a young woman walk passed my desk with her counselor, she saw my name plate and said, “That lady is the reason why I’m here”, and I poked my head out of my office, and I remembered – I helped her while she was still pregnant and using heroin. She had been refused MAT by her doctor, and got sick with kidney failure and her doctor dropped her 3 weeks before her due date! It pissed me off so much I went rogue, I emailed everyone from the deputy chief state medical officer to individual doctors and outreach workers. I stepped on some toes, but I didn’t care. A doctor in our community stepped up and took care of her. When I saw her that day, I knew it was all good at least for that moment, she had just had her baby and was a few weeks out. She later brought her baby in and she was beautiful and healthy.

To be clear this woman was always a good mom even when she was using drugs. She always worked to keep her kids safe and as stable as possible.

What continues to motivate you to do harm reduction work?

People are counting on us. I want to leave this world better for my daughter. I am committed to the pursuit of true justice for people.

In these turbulent times, what words of motivation can you share with the wider harm reduction community?

Handle It! That is what we do, no matter who is in office. No matter how bleak the circumstances are. We bring the remedy and the healing. People who use drugs, Harm Reductionists, Outreach Workers, we are the cockroaches that will always survive the apocalypse. We are resourceful. We are like water, we get in everywhere and there is no stopping us. We freeze, we expand and break apart systems. When we boil watch out we will cook your ass. Water heals and cleanses and we also soothe and heal. We might get discouraged, but we adapt and never lose sight of our goals. We are not bound by normal conventions. People are counting on us, handle it!

When it comes to racial justice and its intersection with harm reduction, you know, there has been a lot of criticism because a lot of white men brought traction to this movement, but this work – it has always been rooted in the work of marginalized people. I’m really encouraged with Monique Tula’s leadership, and this is a time of transformation, and I want to continue to be a part of it. I appreciate the contributions of white men who used their position to bring harm reduction to a place where it was more widely recognized. Women and other marginalized people have always been doing the work.

We need to be starting conversations that no one else is having. People of color, and especially the women of color who have been doing this work, we’ve always been the ones pushing the buck, and it’s encouraging that we’re in positions of leadership now and I’m really excited for where this movement is going.

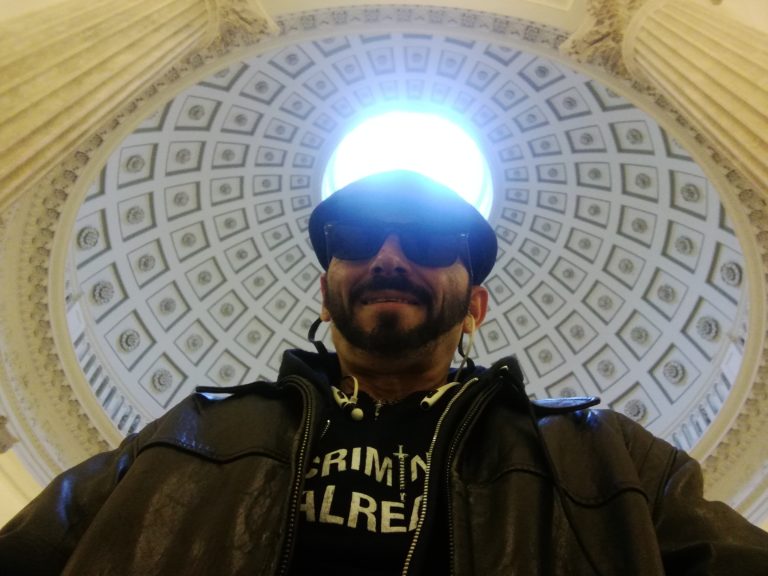

Rafi Torruella, Executive Director, Intercambios, Puerto Rico

Please tell the harm reduction community a little about yourself.

I’m just a guy that grew up here in Puerto Rico, seeing a lot of drug use and seeing people who use drugs being judged for what they do. I’m the Executive Director of Intercambios Puerto Rico, the largest syringe exchange by volume here, but we are very low key, and serve many communities as much as we can – we strive to be consistent, persistent, and present. Harm reduction is revolutionary love, and it’s very real, and it’s very concrete. At Intercambios we try to embody that as much as possible by creating this loving space, and really caring for people. We are here in solidarity with the communities here. At Intercambios we do 4 things as best as possible:

- Syringe access: because this is the lived reality of people we are beholden to and that’s our core. We serve 19 communities and have been exchanging over 250,000 needles a year. We also provide HIV testing, referrals for health and mental health services, mobile syringe exchange services. We use a peer model, and our peers are staff personnel with full jobs and responsibilities. This is incredibly important to us, the peer model is a viewpoint and way you work from, and it’s a strength of ours.

- Drug policy: because harm reduction is not just services or a model, it’s about engaging the service side of our program with the policy side of harm reduction by educating clients who can then educate and organize each other. The policy side of our operations is about educating the community and politicians, and really carving out a dedicated drug policy campaign here.

- Human rights: reporting on court cases taking place regarding the humiliation and abuses in drug treatment programs in PR that use a moral model that is breaking the human rights of individuals.

- Technical assistance: for harm reduction policy and services throughout the Caribbean and South America in places like Dominican Republic, Colombia, and St. Croix.

How did you first become involved in harm reduction and drug policy reform?

My mom has always been pro-independence, and this always kept me thinking a lot about how we get out of this mess – colonization and the lack of a coherent drug policy. I learned about the concepts of harm reduction one day while I was at the school of public health, I was working at the university at the time doing research for NIDA and the whole “hijacked brain” thing was everywhere in addiction research. Then, my grandmother showed me a newspaper article featuring a syringe exchange program and said, “Hey there’s these guys here doing what you’re always talking about”, and it slapped me in the face because there were these people doing this thing I had always talked about. There’s this beauty of harm reduction services that it brings the humanity to the issue.

What are the current challenges for harm reduction in Puerto Rico?

The biggest challenges here? It’s being a colony – it’s hideous. We’re not a state, and we’re not a country. It’s a neoliberal dream. Nothing ever moves forward. There’s no viable system for evidence-based treatment. Colonialism is one of those hungry ghosts that keeps us Puerto Ricans seeking for a way to grasp some type of control over our destiny. We don’t have many of the systems other people have. We don’t have the right to vote for the person who is to become our president (U.S.) and we don’t have a vote in Congress, not even in lowly committees! We have no voice, and there is no democracy.

Right now, our challenge is being able to meet the needs of people. We want to know more. Our challenge right now is to scale up treatment access to buprenorphine and methadone, and increase funding. Political social and economic instability are challenges. Resources and fundraising are challenges. The trauma is real, and it’s not going to go away from one-shot donations. A low-threshold clinic is needed – we need resources – how else do you take these harm reduction services and bring them to the streets and to the community?

Puerto Rico has had syringe vending machines since 2009. Can you tell us more about them?

We don’t have one at Intercambios yet, but I’ve visited all of them. They are mostly supported by AIDS United. They are good as a supplement to a program, but they are no substitute to an actual harm reductionist and the resources offered by a program. I can put my coins in a machine and get my kit, but in reality, they function best as a compliment to a Syringe Access Program. They pay for themselves once they are implemented. The numbers are good, and they’re getting used. The machines are located at syringe access programs, so the NIMBY effect isn’t really an issue and the wider community is not really exposed. The people at large, in town and in the country, understand that this is a public health intervention, not an enabler.

What is your most memorable experience doing harm reduction work?

One day working at City Wide Harm Reduction watching somebody open their eyes after naloxone had been administrated for an overdose. I’m closer to a person that’s alive than somebody who died of an overdose. What was most memorable was being able to come back to my home, Puerto Rico, and do the harm reduction work I wanted to do here – that’s beautiful – being able to do that revolutionary love action here in Puerto Rico.

What continues to motivate you to do harm reduction work? Any words of motivation you can share with the wider harm reduction community?

It’s about love, that revolutionary love, it’s something that you give. It’s social justice that’s what motivates me – giving and receiving that love that is bound by social justice. It’s very respectful, and interpersonal. It’s intimate. It’s about blood, it’s about getting high, it’s about safe sex, and that is really personal.

Any final comments?

We need to understand ourselves, harm reduction, as a social movement, not just a community. There’s a lot of intersection in our community, and even for the non-drug user that is extremely affected by the war on drugs and doesn’t see it. We’re in the middle of a lot of issues. I think we’re talking about incarceration, immigration, decolonization, sex, race, and class (it’s always about class struggle!). It’s in the middle of so much, and we shouldn’t be limited. It’s a way of engaging. It’s a lot and it’s huge, it’s not just one angle and we have to execute that through time and different relationships.

Harry Leno, Harm Reduction Pioneer and Founder of Love & Safety, Massachusetts

Please tell the harm reduction community a little about yourself.

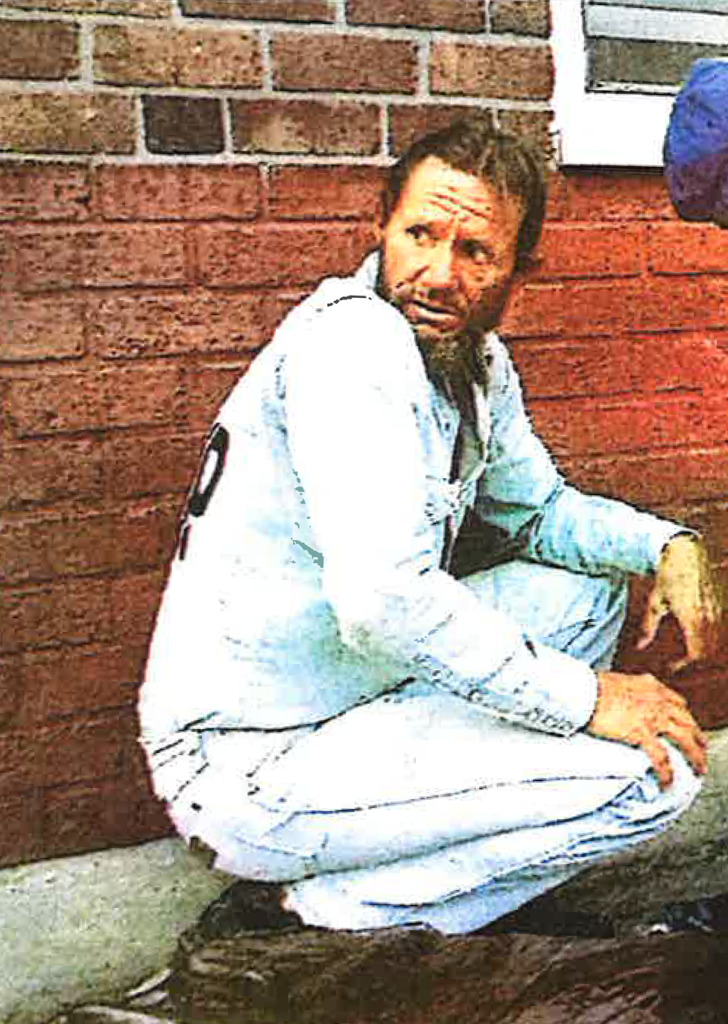

I’m Harry Leno from Ipswich, Massachusetts. I have worked for the Animal Control department in my town for most of my life. I have several great grandchildren that I’m looking forward to spending time when I retire later this year. I’ve been doing street-based syringe exchange since the early 1980s throughout Massachusetts, Connecticut and New York and on a weekly basis for more than 20 years in Lawrence and Lowell, MA. By ‘street based’ I mean that I operate out of the back of my car, from which I distribute sterile needles and health care kits with associated products. Other than being off the street briefly last year when I had a hip operation and another time when I traveled to South America for a period of about three years I have not missed a single week of being on the streets. My operation is called ‘Love and Safety.’ I have self-funded my activities to the tune of about 90%.

How did you first become involved in harm reduction?

When HIV/AIDS started showing up in the early 1980s and a group called ACT-UP was beginning to organize to help address the crisis, I saw a flyer in a local bar that read: “800 people have died – what are you doing to help?”. This flyer pushed me to call my sister who was part of the LGBTQ scene. She explained that a lot of people were dropping dead of this mystery disease and no one really knew what it was, except that people who shot drugs and gay men were the worst hit by it. Not long after talking to my sister, I attended a lecture by the Black Rose Anarchist Group about HIV/AIDS and people who inject drugs. It was such a heartbreaking time, one week you would see somebody when you were giving them clean needles, then the next time you see them they would be 10-20 pounds lighter and then you see them again a few weeks later and they’re dying in a shelter or hospice.

It was just unbelievable to me, just unbelievable how people weren’t paying attention – all these people are dying and where are you? I asked myself. This is a community that was being totally sidestepped. I was really struck by how many people were dying in the streets and no one was doing anything to help them. As a result, I became more involved with ACT-UP’s work around needle exchange and began doing mobile needle exchange out of my car in early ‘80s in the tri-state area – first in Boston, then around New Haven, and then in New York City. I would finish up work at Animal Control on a Friday night, and then drive to New Haven to do needle exchange while staying the night in a storefront where they organized ACT-UP meetings.

On Saturday morning I would wake up and drive to NYC and do needle exchange out of my car in the 5 boroughs and drive back up to Boston on Sundays before heading home to Ipswich to start my work week again on Monday at Animal Control. This was my routine for years and years, and I would get harassed by law enforcement regularly – I even lost my car to the police impound. I kept on because I just really loved ACT-UP, especially in New York City. ACT-UP was a real sacred protector of their people in the community. I just remember thinking to myself, these people who shoot up and come to get sterile needles and start taking care of themselves – a lot of these people are better off than people on alcohol because there’s just so much love in harm reduction.

What is your most memorable experience doing harm reduction work?

For me, it’s not so much the experience of giving people sterile equipment, it’s the people that I remember. I miss the people who disappear and don’t come back. When people do come back, and you hug them – it reminds me that harm reduction is all about the love.

What continues to motivate you to do harm reduction work?

I just love the people and the love that they give back. Just love for the people – period. It’s just tragic, you know, the way people who use drugs are treated by medical professionals, particularly doctors in hospitals. With harm reduction, no matter what, it’s just love and support – and people who use drugs just don’t have that when they go to ask for help somewhere else. It’s tragic. With harm reduction, with syringe exchange it’s just a whole lot of love, giving so much love to people.

In these turbulent times, what words of motivation can you share with the wider harm reduction community?

There is an underserved community of people at risk on the streets. They constitute a public health risk that is not addressed by the formal network of harm reduction. There is a role for the street based approach, and it is distinct from the formal exchange programs. So my words of motivation are…hit the streets, and serve the community that is not likely –- for reasons of stigma, or immigration concerns, or other–to become part of the formal exchange programs which are often presented as the answer to the public health concerns addressed by needle exchange as I have practiced it for coming on 40 years in the name of Love and Safety.

It’s just all about the love, you know. I also want to thank David Flood for his assistance with the interview.

Rajani Gudlavalleti, Community Organizer, Baltimore Harm Reduction Coalition

Please tell the harm reduction community a little about yourself.

I am a proud second-generation Asian Indian Telugu-American, dark-skinned queer-cis-woman. Growing up in the beautiful but heartbreakingly expensive San Francisco Bay Area, my family stayed strong even when faced with job losses, evictions, and the broken health system. In 2009, I moved to Baltimore to earn a Master’s in public policy, focusing on gender-specific and racially equitable approaches to criminalized issues. Currently, I am the community organizer for Baltimore Harm Reduction Coalition, coordinating BRIDGES, Baltimore’s grassroots movement for safer consumption spaces. I am also a trainer with Baltimore Racial Justice Action, co-organizer of Baltimore Asian Resistance in Solidarity, and board member of Foundation Beyond Belief. Most importantly, I love bunnies and Star Trek.

How did you first become involved in harm reduction organizing?

I’d like to say that I’ve always been doing harm reduction work, I just didn’t know it. The first place I heard the term “harm reduction” was as a graduate intern at Power Inside, a direct service and advocacy organization that serves women and girls in East Baltimore. There I learned that harm reduction, racial justice, and all forms of anti-oppression work are intrinsically connected. Since Power Inside, I have dedicated time to criminal and juvenile justice reform at OSI-Baltimore, overdose prevention with the city health department, LGBTQ+ organizing with a variety of community groups, and racial equity education with Baltimore Racial Justice Action. Harm reduction philosophies have carried me through all of these spheres, so it felt like a natural and timely fit when local SCS advocates were looking for a community organizer to build a movement for Baltimore.

Can you please tell us more about your work with stakeholders in Baltimore to promote a racial justice vision in the implementation of harm reduction services?

“Nothing about us without us.” This is an anti-oppression activism concept that guides the BRIDGES Coalition in our work to build grassroots SCS support in a city that has been devastated by the racist War on Drugs. Over the past year, we have built up this coalition with leadership from a variety of community organizations that are all dedicated to racial justice approaches to harm reduction, including people who use drugs, people in recovery, medical practitioners, community organizers and other passionate advocates. We conduct outreach, provide public education, and offer community members a place to unpack their thoughts, questions and concerns about SCS and harm reduction.

What is your most memorable experience doing this work?

I love engaging people in firey conversations about the War on Drugs, especially when I am privileged to observe fellow people of color grow empowered to fight racism and advocate for our communities. I get to experience this often during our community dialogue events, which we call “Seeking Safety in a War Zone.” At these events, we bring together community members to learn about and discuss: the racist history of the War on Drugs, harm reduction as a means of increasing safety, and SCS as a tool to prevent overdose and over-incarceration. At the first of these events back in August 2017, we were in the Penn-North area, which was prominent during the Baltimore Uprising in 2015. Almost 60 people attended, which was a wild surprise (I was expecting like 30 people)! Folks were so engaged in the conversation, and while we may not have convinced all 60 to support SCS, we had a powerful conversation with a largely POC crowd. I knew in that moment that I had the best job.

What continues to motivate you to do harm reduction work, and what words of motivation can you share with the wider harm reduction community?

I work with the most amazing people who motivate me to stay optimistic, even when I’m enraged by weak-willed politicians who’d rather stay in office than save lives. To the wider harm reduction community, I say, our mere existence is resistance, and we must stay vigilant for the sake of justice.

Any final comments?

I am so excited to be part of a movement with women of color in leadership roles–it’s about damn time. Black and Brown people, particularly women and queer folks, have been practicing harm reduction since the first colonists, imperialists, and enslavers showed up in our lands. The harm reduction movement must continue to acknowledge this expertise across the field if we are to truly be a movement rooted in dignity and respect. With that said, thank you to the Harm Reduction Coalition for asking me to share my voice and everyone who encouraged me to jump into harm reduction with both feet!

Please tell the harm reduction community a little about yourself.

I’m a native New Yorker and grew up poor as hell. The people that had money and had food in my neighborhood were the ones selling drugs. I was a drug dealer. Good people do bad things, it doesn’t make you a bad person. Through dealing I learned about harm reduction and have been working in the field ever since. These days I go around New York and other and cities testing for fentanyl and teaching people how to test, use safer. I also try to train everyone I meet about overdose reversal.

How did you first become involved in harm reduction?

My past made me who I am today. It was really by accident. I ran into a friend I hadn’t seen in a while who needed to get syringes. I went with them to a syringe access program and while they were getting supplies, I started chatting with a staff member. This person changed my life. They told me all about sterile syringe distribution and working to keep people healthy and alive. I got hooked, I thought it was the greatest thing I’d ever heard! Taking care of people who use drugs and helping them out. After only ever seeing how fucked up people who use drugs are treated by everyone from welfare to the medical profession, it was a complete transformation for me.

What is your most memorable experience doing harm reduction work?

There has been countless. This is probably not what people want to hear, but my very first reversal. I saved someone from dying. That had a huge impact on me, and so many reversals after and still, I’m in awe when I see/hear that first breath coming back to the person. I stopped counting my reversals in 2010, and then I was at over 75 reversals. The first person was literally about an hour after being trained so it was very scary, but the thought of the person dying was even much scarier.

If you had one “take home” message about fentanyl, what would it be?

Fentanyl is not going away, it’s only going to get worse. We need a harm reduction approach.

What continues to motivate you to do harm reduction work?

Life. Trying to help people stay alive. No one should die because they use drugs. So that motivates me, knowing that what I do has the potential to save lives.

In these turbulent times, what words of motivation can you share with the wider harm reduction community?

Keep doing what you’re doing, think outside the box, and don’t let the law define what you do or stop you from doing what you do, because most times we must work outside these archaic laws to help people.

Any final comments?

Drugs are here to stay, and no matter what people will continue to use. It’s time to take away these moralistic views and do the right thing, which is helping people stay safe, healthy, and alive. I don’t think what I’m doing is the solution to the problem, I don’t think I’m going to save the world, what I do think is that I’m saving lives and every little bit counts. Do what you know best and go at it hard. It takes all of us and we all need to work together. Really there is not much more I can say, but that everyone deserves a shot at life and if you can help save one person, you’ve done a lot, but don’t stop at just one.

To support Tino’s harm reduction work on fentanyl testing, please consider donating to his GoFundMe page.

Angie Gray, Harm Reduction Program, West Virginia

Please tell the harm reduction community a little about yourself.

I am the Nursing Director at the Berkeley County Health Department in Martinsburg, West Virginia. I taught Community Health clinical for Shepherd University’s bachelor of science in nursing (BSN) program from 2009-2011. Since 2013, I have also served on the Morgan County Board of Health as the elected chairperson. I am a Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Public Health Nurse Leader; and a longtime member of the West Virginia Public Health Association, I have served in many elected roles on the Nurse Executive Committee. Growing up in West Virginia I faced many of the disparities that West Virginia’s still faces today, I realized at a young age that we don’t all start out on an even playing field. I am dedicated to the health and well being of all West Virginians.

How did you first become involved in harm reduction?

Being a public health nurse, I always say I have a front row seat to what is happening in our community, many times long before other entities even recognize there is an increase in certain health issues. In STI clinic, I saw an increase of people who inject drugs and they would ask for help, but due to the limited behavioral health capacity in West Virginia, the option was a 3-6 month waiting list. The frustrations of this lead me to look for ways to help. I saw harm reduction programs as a way I could give support and vital disease reducing supplies and concepts.

What is your proudest moment or most memorable experience working to reduce drug-related harms?

My proudest moments are when I am discussing concepts of harm reduction with someone who is totally against harm reduction, and views it as enabling, and I see that ‘aha’ moment come across their face. When they walk away a believer I know it was worth the fight.

A memorable experience was when a participant, after being asked if there was anything we could do better, stated “No, you guys are great! Better than Baltimore City Harm Reduction Program.” We all know the great reputation of Baltimore’s harm reduction program, so of course I was feeling pretty good. I asked the participant what made our harm reduction program better than Baltimore. The participant replied “Your cookers have handles”. Small things make all the difference!

West Virginia is the state hardest hit by the opioid crisis. What continues to motivate you to work there?

After participation in our harm reduction service, a grown man walked out and through the lobby with tears running down his face, because he was treated with respect and as a human being. Moments like these, fuels my determination to continue to do harm reduction work in the state.

Given that you’re working against such incredible odds in West Virginia, what words of motivation can you share with the wider harm reduction community?

Slowly, but steadily, we are making a difference.

Any final comments?

Finally, I would like to add that connecting to Harm Reduction Coalition was invaluable to obtaining our goal to open a comprehensive harm reduction program with syringe access. Special thanks and much gratitude to Joanna from Harm Reduction Coalition!

Haley Coles – Sonoran Prevention Works, Arizona

Please tell the harm reduction community a little about yourself.

First and foremost I’m an Arizonan, and extremely committed to the big, hot, strange state I live in. I have been active in harm reduction since 2006, when I first bleached out a syringe that somebody else had used in attempts to protect myself from HIV. Since then, I have been involved in syringe access programs in Phoenix and Tacoma, WA, created a nonprofit harm reduction advocacy organization called Sonoran Prevention Works, and dedicated myself to engaging with hostile political systems to fight for health equity for Arizonans who use drugs.

How did you first become involved in harm reduction?

In 2010, I was invited to a friend’s house to learn about syringe access programs. Three of us – Nathan Leach, Turiya Coll, and myself (we all still work together on harm reduction projects in AZ) – researched the policies that prevented a program from operating in Phoenix, applied for a startup grant through NASEN, and began focusing on advocacy to change those policies. Within a few months we began outreach to people who inject drugs and potential partners in Phoenix. We figured we’d present the problem to the health department and they’d immediately start working to change policies. What a bunch of idealists we were! We were essentially laughed out of multiple rooms and told that we’d be threatened by law enforcement if we ever tried to set up a program, so we shouldn’t bother.

I never wanted to work within the system – I was just an ex-IV drug user who was into poetry and DIY life. But after repeatedly seeing the apathy, which for me translates into cruelty, of many public health and political leaders in the state, it became clear that I was going to have to suck it up if I wanted to see the kind of equitable change that I envisioned. So I wear heels, shake hands with cops, kiss babies, and search for creative ways to subvert resources to make it into the hands of people who are directly impacted by the violent conditions imposed on them by the state.

What is your most memorable experience doing harm reduction work?

There are so many life-changing experiences I’ve had over the years, but one of the most positive moments occurred just a few weeks ago. The outreach that Nathan, Turiya, and myself started in 2011 has grown into a program that makes 5000 contacts each month with people who inject drugs in the Phoenix area, and is run by about 20 volunteers. At one of the busiest sites, volunteers decided to host a participant and volunteer appreciation BBQ and kit-making party. We made a few thousand kits and burned through 500 hot dogs and burgers. I cooked like a hundred burgers, even though I don’t eat meat. I saw so many new relationships formed between and among participants and volunteers, and the love flowed hard. At that barbecue I was deeply reminded that we’re all in it together, that I’m not free until the war waged on other Arizonans ends, and that I’m incredibly privileged to be involved in such a radical, fearless, and necessary program.

What continues to motivate you to do harm reduction work?

Honestly I’m just a brat. Every time a politician, nonprofit, or whoever tells me I can’t do something, I’m more emboldened to do it and prove them wrong. I also still get to do direct work on the ground, which reminds me of why I put on the fancy clothes and attempt to adapt harm reduction to the values that perpetuate in Arizona. And finally, I’m a bit of a nihilist. I feel pretty hopeless about the world, the future… But equity for people who use drugs in Arizona can be achieved, it really can, and we have many other areas of the country whose footsteps to follow. Harm reduction gives me hope.

In these turbulent times, what words of motivation can you share with the wider harm reduction community?

For me, it’s been about leveraging the new and existing intersections that impact people who use drugs to build a network of accomplices. As certain protections continue to erode, new frontiers and collaborations emerge. Find people who are willing to stick their necks out, people who understand that being ethical requires taking action, people both disturbed and inspired by the state of things, and get to know them. These people can be found in positions of leadership, in government, in healthcare, in the nonprofit field… Bring them into the fold, learn from them, and scheme with them. Nothing can be accomplished by yourself, and not much can be accomplished by endless planning. Get out there and do the shit with your new friends, make mistakes, and do it better.

For more information on Sonoran Prevention Works see: http://spwaz.org/