From “abstinence proponent” to “’ardent protester’ in support of harm reduction”

By: Mike Pomante

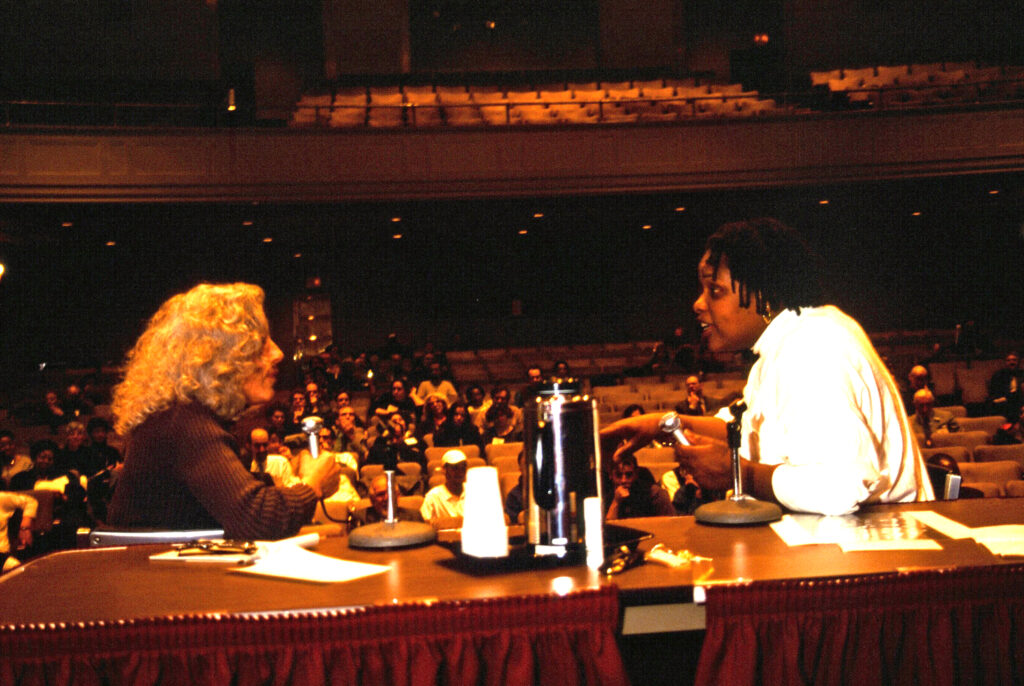

Black history should be taught and celebrated year-round, not just during one month each year. National Harm Reduction Coalition (NHRC) is privileged to continue to highlight the invaluable contributions of Black harm reductionists to the movement while at the same time commemorating and celebrating the vital role of women in harm reduction during Women’s History Month. Today, NHRC proudly spotlights the late Imani Woods, an internationally known harm reduction pioneer, educator, Black community leader, protestor, community builder and connector, and outspoken advocate for people who use drugs.

Imani Woods was born in Bedford-Stuyvesant, known as Bed-Stuy, in Brooklyn, NY, and she dedicated her life to bettering the lives of Black people and people who use drugs across the country. She worked as a civil servant at the Human Resources Administration and was a staunch opponent of needle exchange and harm reduction. In 1989, Woods lost her “soul brother,” Keith, a former intravenous drug user, to a 5-year battle with HIV. Woods and Keith were relenting in their opposition to needle exchange, describing the idea as “ineffective, immoral, crazy, ridiculous.”

Woods, originally a “card-carrying abstinence proponent”, didn’t start doing syringe exchange until 1989 upon witnessing its effectiveness on the streets of Seattle. Once she saw harm reduction in action and working during her first trip to downtown Seattle, Woods began her “conversion from being an outspoken opponent of needle exchange to being a firm supporter.” She became the founder and executive director of the harm reduction organization Street Outreach Services (SOS) in Seattle and was also a founding member of NHRC (then Harm Reduction Coalition).

Woods, who held a faculty position at the University of Washington, underscored the importance of engaging and including people who use drugs in the development and implementation of programs intended to serve them. She rebuked policy makers who inserted themselves in Black communities to implement programs that failed to garner any community input. Woods wrote, “It is critical to match the harm reduction message to the population you are working with.”

Woods, who held a faculty position at the University of Washington, underscored the importance of engaging and including people who use drugs in the development and implementation of programs intended to serve them. She rebuked policy makers who inserted themselves in Black communities to implement programs that failed to garner any community input. Woods wrote, “It is critical to match the harm reduction message to the population you are working with.”

In her article “Bringing Harm Reduction to the Black Community: There’s a Fire in My House and You’re Telling Me to Rearrange My Furniture,” Woods wrote that many Black people felt mistrust over needle exchange because of an enduring history of white supremacy in public health. As examples, she cited the infamous Tuskegee Experiment, the living legacies of slavery, and distrust over racism in response to the HIV/AIDS epidemic as reasons why Black communities were often reluctant to get on board with syringe exchange.

In Shira Hassan’s Saving Our Own Lives: A Liberatory Practice of Harm Reduction, contributor Kelli Dorsey said of Imani Woods and Dorsey’s mentor, Fred Johnson:

In Shira Hassan’s Saving Our Own Lives: A Liberatory Practice of Harm Reduction, contributor Kelli Dorsey said of Imani Woods and Dorsey’s mentor, Fred Johnson:

“[They] invested in building relationships with everyone, including Black leaders, legislators, members of neighborhood associations, gatekeepers, families, drug users, and drug dealers in the city. There were so many people impacted by systemic racism who were angry at the thought of needle exchange, but Fred and Imani were humble, grounded, with an in-depth understanding of why Black folks in DC and other cities across the country felt this way, so they always led with compassion.”

Today, the tenets of harm reduction mimic Woods’ compassionate approach and her commitment to people who use drugs having a real voice in the creation of programs and policies designed to serve them. Woods’ legacy lives on as Black leadership inside and outside of harm reduction continues to be fostered nationwide and the harm reduction movement addresses and heals the harms caused by racialized drug policies.

More links:

Imani P. Woods on Black Leadership and Harm Reduction

Books with excerpts and information from Imani Woods:

“Saving Our Own Lives: A Liberatory Practice of Harm Reduction”

“Undoing Drugs: How Harm Reduction is Changing the Future of Drugs and Addiction”