photo by: thierry ehrmann

February was Black History Month. While some, myself included, believe that Black History Month is essentially a concession made by a government seeking to pacify the masses while maintaining the status quo, it is hard to know how to move forward if we don’t reflect on our past. Our movement is indelibly inked by the blood of our ancestors and the Black Panthers are some of the original harm reductionists. To that end, we want to take a moment to reflect on the Black Panthers’ story and its significance to broader American culture. Given the country’s current political environment, we believe much can be learned from the cultural and political awakening for Black people ignited by the Panthers—as well as the painful lessons learned when a movement derails.

A Childhood Dream

As a GenXer, I’ve often wished I was a young adult in the late ’60s, imagining myself protesting in the streets with other “radicals,” angrily shouting our demands at whoever would listen. As it turns out, I was about a decade too late to join that movement, but in many ways the era defined the woman I have become.

I recently visited the Black Panther exhibit at the Oakland Museum of California. Many of you know that despite being born and raised in California, I’m new to the Bay Area. As a child, I heard my parents speak fondly of San Francisco, my mother, in particular. She didn’t have the means to visit often, but took every opportunity to make the five-to-six-hour trek up the coast from Los Angeles. Shortly after my parents divorced, she met and married someone while he was an inmate in San Quentin. I never knew him, never even met him. They made plans for her to move us up to Oakland once he got out, but it never happened. Their marriage didn’t last long, and I don’t really know what became of him.

I often wondered what my life would’ve been like had we moved to the Bay Area when we were kids. I’d heard that people from all over the country left everything they knew to make a new home in the land of free love, free drugs, and free sunshine. They grew their hair long, adorned themselves with flowers, and made love, not war. San Francisco, and Oakland by proxy, seemed to the epicenter of radical love and freedom. I imagined myself living in the Oakland hills without ever having seen them, surrounded by thousands of “mixed kids” of multiracial parents and never again having to answer: “What nationality are you?” Then I saw Angela, and my fate was sealed.

Awakening

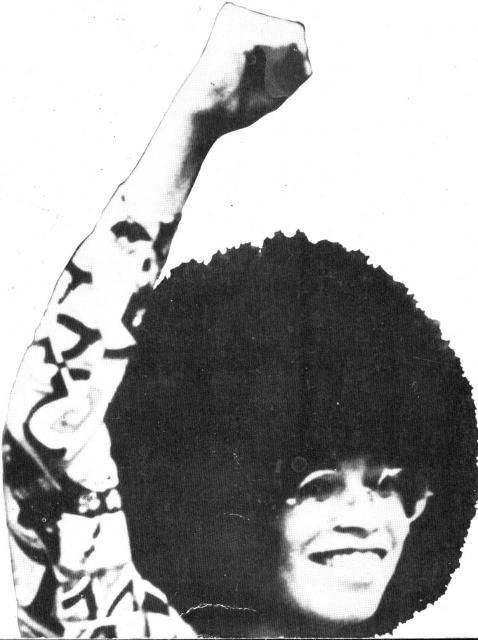

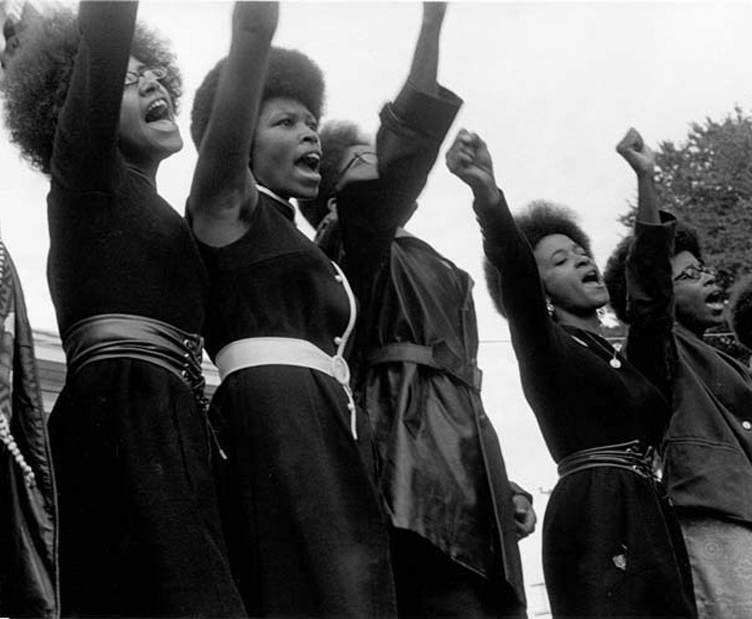

I was maybe six or seven years old the first time I saw Angela Davis. As she walked across the courtroom with her fist in the air, she imprinted herself upon me. Mother Duck. I fell in love with her big, bouncy afro and broad, gap-toothed smile. She radiated strength, power, and resistance. And if for a second you doubted her blackness because of her light skin, the moment you looked into her eyes, she dared you to think she was anything other than the fiercest of African queens. Y’all, when I tell you this sister gave me life!

Looking back, I realized that Angela—by virtue of her broadcasted image on a screen—introduced me to a new archetype that day. I saw in her something I wanted: her terrible beauty, her battle scars, the power she held in her fist. Although Angela wasn’t officially a Panther, she, alongside Elaine Brown, Assata Shakur, Kathleen Cleaver, and all the lesser known, but equally powerful Panther sisters—stood in the face of the patriarchy as unapologetic Black women, committed to the total elimination of social-and-economic disparities and institutional violence perpetrated by a white, capitalist government.

Besides my own biological and chosen family, the most influential Black people in my life are still the Black Panthers. These beautiful, courageous, and fallible human beings sought to transform the system of racial oppression by staring the opposition in the face and show that the exercise of power would not go uncontested—not unlike our own family of harm reduction warriors.

The Original Harm Reductionists

Tired of waiting to be saved or treated with equity, the Black Panthers brought a new message of self-determination. Beginning in Oakland, the Panthers began serving full, free breakfasts to children. Soon they were serving 20,000 school aged children in 19 cities around the country, and in 23 local affiliates every school day. In 1972 Elaine Brown updated the Black Panther Party manifesto to include an explicit demand for free healthcare for all black and oppressed people. First and foremost, the Panthers advocated for preventive health care and noted the importance of health literacy to the overall vitality of poor Blacks.

“We believe that the government must provide, free of charge, for the people, health facilities which will not only treat our illnesses, most of which have come about as a result of our oppression, but which will also develop preventative medical programs to guarantee our future survival. We believe that mass health education and research programs must be developed to give Black and oppressed people access to advanced scientific and medical information, so we may provide ourselves with proper medical attention and care.”

Nothing about us without us.

Harm Reduction: A Cultural Shift

The ‘80s gave rise to a different kind of activist who forced the American government to confront its shameful abdication of leadership over the AIDS epidemic. A small group of visionary people took it upon themselves to advocate for people who use drugs, and as a result, we witnessed the birth of an entire community of advocates, activists, practitioners, and drug users. We created our own manifesto of sorts: the Principles of Harm Reduction. Over time, we figured out how the machine works, got inside it, and in spite of our spiky hair and dreadlocks, we created change.

Thirty years later, harm reduction and sane drug policies are making their way into the mainstream. Soccer moms and lawmakers alike understand the phrase “if people don’t get their needs met, they struggle to get their needs met,” and more importantly they are beginning to “meet people who use drugs where they’re at.” This cultural shift has led to kinder, gentler public health approaches to complex, intersectional problems.

Our Current Reality

Today, people who use drugs and their advocates, like most of the nation, are headed into an especially turbulent and contentious time. What we’ve always feared is becoming a reality:

ICE is knocking on doors in SoCal and across the country looking for people to deport. Undocumented needle exchange participants in Austin, Texas, are being told to send someone else to the program in their place because ICE is targeting the van. We’re seeing a revitalized drug war, shrinking access to abortion and reproductive health care, and increased criminalization of pregnant women who use drugs—especially if they’re poor and/or black and brown. The ongoing opioid epidemic is ravaging entire communities similar to the ways in which crack did in the ‘80s and ’90s. Speaking of the ’90s, sentencing disparities persist along with felony disenfranchisement. And then there’s the Affordable Care Act (dis-affectionately known as ‘Obamacare’), which is at imminent risk of being dismantled. Let’s not forget that the ACA not only provides healthcare coverage for tens of millions of people, but it also created jobs in communities all over the country for people who are systematically denied both.

Woke AF

On November 8, 2017, the United States woke the f**k up after what seems like a thirty year-long nap. During that time, the conservative right was organizing. They homeschooled their children and fed them a diet of fear-based rhetoric. Once these young people were old enough to hold a clipboard, they marched into suburban and rural neighborhoods, knocking on doors and campaigning for candidates who represented their “American values.” This strategy worked: the far right is closer to power than they have been for decades.

The Panthers created a bold vision with a long-term strategy to get there. They knew the likelihood of their success, as well as their demise, but nevertheless, they persisted. The endurance race ahead of us consists of redirecting the hegemonic vision of the current administration, which is not unlike the vision the Panthers sought to destroy. We must counter the narrative that Muslims are a danger, Mexicans are overrunning the borders, and closer to home, that drug users are bad people who lack a moral compass. This stigmatizing rhetoric does nothing but keep us distraught, distracted, and divided.

What’s Our Long Game?

The election results have shaken many social justice advocates to our core. The rise of xenophobia and intolerance on many levels is affecting the politics of countries all over the world. We are all living in a precarious moment that will define us for decades to come. We don’t have time for navel gazing or arm-chair activism. The time to act is now. What lies ahead of us is an endurance race, not a sprint, and compared to the right-wing conservative movement, we are woefully out of shape.

Like the Panthers, harm reductionists believe that everyone has the right to health and well-being. Everyone has the right to participate in the public-policy dialogue. To achieve this ideal in the midst of social and political upheaval, we need a multi-pronged strategy that includes refined advocacy as well as confrontational activism. We need to build an army of young leaders who understand these values and will fight for them.

Resistance is more than a hashtag. Resistance extends beyond protest signs, strikes, or marches. Resistance is the willful act of refusal—former acting Attorney General Sally Yates is a great example of this. Resistance will surface in the conflict between the different branches of the state, and it’s up to each of us to hold these branches accountable. If the current administration is testing anything, it’s testing how far it can go before the other branches say enough. And my fear is that they won’t unless we the people demand they do.

Where Do We Begin?

With each other. Recently, a group of Bay Area harm reductionists took the first step of our marathon training. Gathered together in a small, sunny storefront on Telegraph Avenue in Oakland, we shared our hope, fears, and talked about how to be part of the solution. We agreed that the Panthers were right: that people united, can never be divided. We decided to focus our efforts locally because we believe this is where we have the most power. Someone volunteered to figure out where our local town halls are happening so we could have face-to-face conversations with our elected officials. We decided to find other local groups to partner with because black lives matter as much to us drug users’ lives, and because San Francisco—like all the country’s sanctuary cities—is under attack.

Reflecting on that afternoon, I realized my childhood dream was coming true. Right here in Oakland, CA: home of the Panthers, birthplace of the revolution.

Power to the people.

-Monique Tula